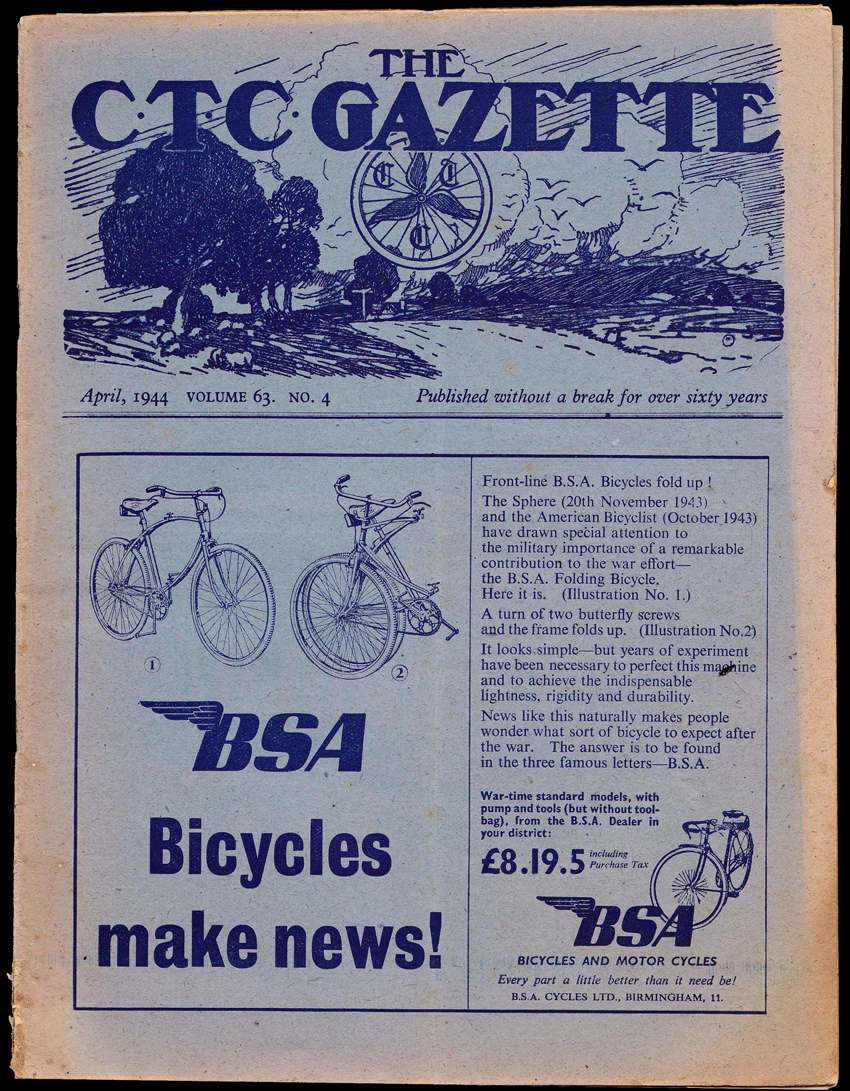

the BSA Airborne Paratrooper Bicycle, 1944

On yesterday's photo of the landings at Juno Beach soldiers appear to be landing with bicycles. I thought when I saw it how far we have come from bicycles to drones in the conduct of war, given that some of those fellows in the photograph are probably still alive: many of them died that day however.

The bicycles: BSA [British Small Arms, a Birmingham manufacturing conglomerate that made everything from rifles to London taxis] made 70,000 Airborne Folding Paratrooper Bicycles between 1939 and 1945. As with all things military there are many sites devoted to the most arcane details of this bike, its rifle holder, its pedals, its colour (green). This one is very complete: Bcoy1CPB which will mean something to anyone connected with the Canadian Forces: B Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion I think.

In the D-Day landings, the bicycles were to be used by the second wave regiments to speed their way to the front, but the troops found the roads so congested that they couldn't ride and most were discarded. B Company reports that they were intensely disliked: probably weighed a ton, and after the war many were sold as surplus: $10 though the Hudson's Bay Company, $3.95 at Capital Iron in Victoria, BC.

Oh, Capital Iron, a most wonderful weekend tradition of my childhood: huge, dark and gloomy, smelled like metal, oil and canvas, aisles of barrels of nails and tools and incomprehensible metal doodads. The ceiling was dense with hanging flags. I suppose it also operated as a reality check, all that metal and machinery, for the men who miraculously found themselves in clean safe jobs with little families and houses with back yards just ten years after the end of the war.